Understanding a company’s financial blueprint often boils down to a few key numbers. One of these is the Debt-to-Equity (D/E) Ratio, a measurement that, while seemingly simple, offers a deep dive into how a company finances itself, mixing debt with equity, and ultimately gauging its leverage and associated risk.

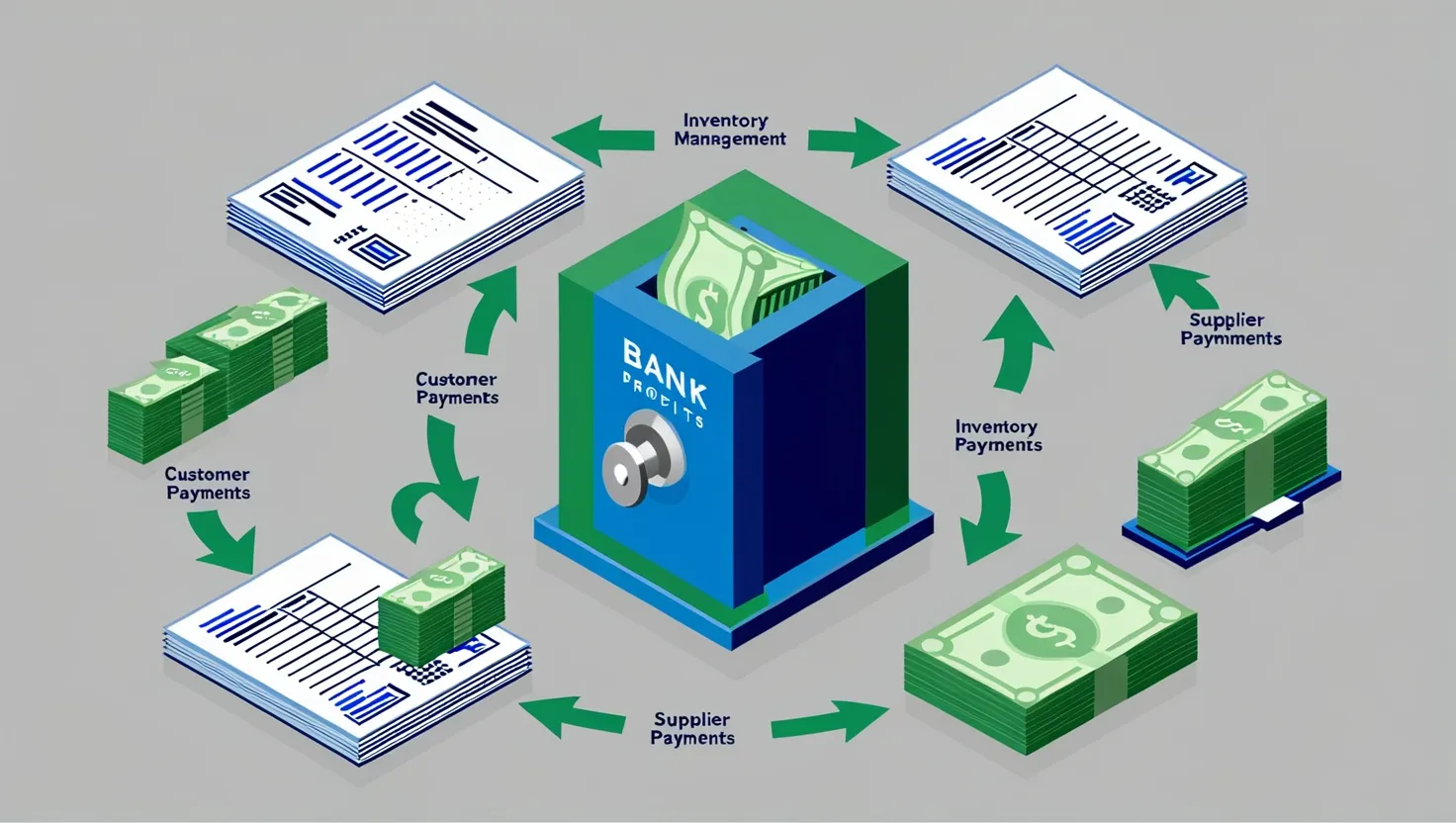

Grasping the D/E Ratio is akin to getting a comprehensive snapshot of a company’s financial skeleton. You tally up all the company’s liabilities and divide them by the equity possessed by shareholders. This exercise tells you why a company might appear heavily in debt or cushioned by equity. Imagine a company with $50 million in liabilities and $120 million in equity - the D/E ratio sits at 0.42. This implies, for every dollar of equity, there’s 42 cents in debt wielded by the company.

Why should this number matter to anyone besides accountants and financial wizards? Well, a lot rides on this particular figure. It’s a crucial lens into the company’s capital mix. Should the ratio be sky-high, the company leans heavily on debt, which can be a precarious gamble. Conversely, a lower figure means less debt dependence and a potentially firmer financial grounding—very much peace of mind for investors and analysts alike.

However, once you start interpreting the D/E ratio, the waters get a tad murkier. There’s no all-encompassing ideal ratio because industry norms vary wildly. Utilities, for instance, often flaunt lofty ratios due to their mammoth infrastructure expenses and consistent cash flow. On the flip side, tech giants generally operate with lesser ratios, thanks to lower capital requirements. Take Apple in 2023 as a case in point. With liabilities towering at $290 billion against $62 billion in equity, its D/E ratio was above 4.6. For many industries, that screams high risk, but Apple’s steady cash flows and strong financial pulse put it in a snug spot.

Each industry carries its peculiar D/E quirks. Banks and financial enterprises often showcase high ratios—as these businesses flourish on borrowed money. For them, elevated debt levels are par for the course. Meanwhile, firms in consumer staples might also display high ratios thanks to steady revenue streams despite their slower growth.

Yet, even the handy D/E ratio isn’t without its flaws. The main hiccup centers on defining debt. Preferred stocks often straddle between debt and equity due to their fixed dividend traits. Classifying them sways the ratio calculations dramatically, painting vastly different pictures of financial health based on how they’re accounted.

So, what would a “good” D/E ratio look like? In a sweeping sense, figures under 1 are routinely seen as safer, whereas numbers nudging 2 or beyond might flash warning signals. However, this perspective is heavily slanted by industry benchmarks and individual company strategies. A D/E ratio of 1.5 could trigger alarm bells in one sector but seem perfectly balanced in another. It’s all about juxtaposing the ratio against industry rivals to gauge where the company stands.

The ratio also offers insights into a company’s fiscal wellbeing. High numbers can quantify elevated financial risks due to the towering debt commitments. Such circumstances could spike interest expenses and complicate debt coverage, particularly in economic slowdowns. However, don’t too quickly celebrate a rock-bottom ratio; it might mean the company is steering clear from debt, possibly missing out on cheaper financing options or tax breaks tied to interest payments.

Consider a real-world example: Two companies, one in tech and the other in utilities. The tech firm sports a D/E ratio at 0.5, whereas the utility firm’s figure is 2.5. Initially, the utility company’s higher ratio might signal risk, but once industry patterns come into focus, it seems just another day at the office—reflective of their regular cash flow and significant capital spends.

Investors curiously eye the D/E ratio to gauge company risk and health. Conservative investors might shy away from high ratio firms, favoring less debt-laden options. Meanwhile, aggressive investors could be tempted by the prospect of high returns tied to companies leveraging debt for growth spurts.

Ultimately, the D/E ratio is about balancing risk with reward, amplifying gains during economic booms, while potentially deepening losses in downturns. Companies strive to find a sweet spot, harnessing debt judiciously to fuel growth while safeguarding an equity backstop for ongoing stability.

Practically speaking, the D/E ratio is a pivotal compass guiding strategic financial decisions. Should a company contemplate large-scale expansion, deciding on whether to capitalize through debt or equity becomes critical. A high D/E might ensure temperance before incurring more debt.

This ratio isn’t merely a statistic—it’s a vital toolkit element for investors and company strategists alike. It sharpens understanding of a company’s financial leverage and hazard profile, guiding informed decision-making about corporate health and growth potential. Even beyond corporate realms, these principles pepper personal finance decision-making, from evaluating home loans to car finance.

In conclusion, while fiscal management may not mingle directly in everyone’s daily grind, the Debt-to-Equity Ratio offers wisdom beyond boardrooms. It frames a fundamental understanding of risk, balancing debt against equity—providing insights into a broader financial strategy that matters whether dwelling at home or dealing with global conglomerates.